The global and Canadian economies are in the midst of the worst recession since the Great Depression.

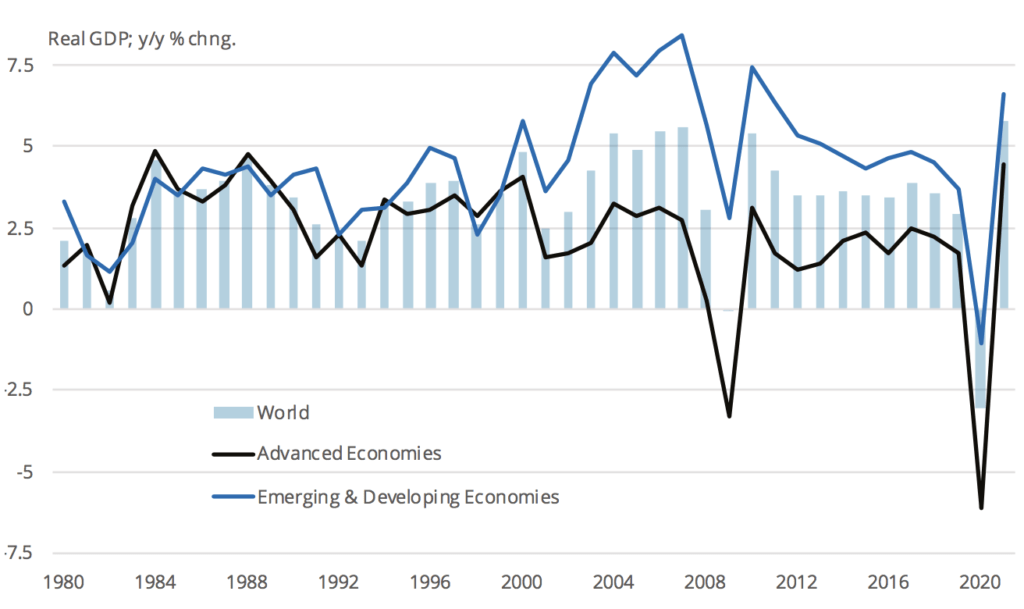

The IMF is projecting the world economy will contract by at least 3 percent this year, a sharp reversal from growth of 3.3 percent anticipated in January 2020. To appreciate the severity of the current downturn, one need only consider that the global economy merely stalled (-0.1 percent) during the Great Recession of 2008/09 (see Figure 1). For advanced economies, like Canada, the downturn looks to be twice as deep as the 3.3 percent dip in 2009, while emerging economies in aggregate will experience the first decline in output on record. Fortunately, the tide appears to be turning, with growth expected to return in the second half of this year and through 2021.

The economic fallout has been dramatic to date. As the COVID-19 virus morphed from a local epidemic to a global pandemic, governments around the world implemented containment measures such as “stay-at-home” orders and shutdown non-essential businesses. Global trade stalled as economic shutdowns (existing or planned) severely disrupted supply chains and took a bite out of demand. The fall-off in demand exacerbated the imbalances in commodity markets and pummelled prices. Oil prices were particularly hard hit with supply initially relatively unaffected while demand plummeted as transportation ground to a halt.

One of the most unique and defining characteristics of this downturn is that, while both contracted greatly, service-producing industries have been more severely impacted than the goods-producing sector. The service sector’s high labour intensity and close human contact has only intensified the surge in the unemployment rate. The toll was particularly hard on lower paid service workers because of their high concentration in tourism, retail, hospitality, and food services industries. This downturn has also been harder on women, who make up a higher share of the workers in the most affected sectors.

The collapse in economic output and spike in unemployment have been swifter than ever before. Fortunately, so has the rapidity of the policy response. Around the globe, central banks have deployed significant monetary stimulus through lower interest rates and/or asset purchase programs. Monetary authorities have also injected liquidity in money markets to ensure the flow of credit. On the fiscal side, governments deployed income support programs for workers and financial aid to businesses. These actions helped lower the economic downside risks, including the risk of a protracted downturn (depression) and/or deflation.

Figure 1: Global economic growth over four decades

Don’t judge a recovery by its headlines

Due to publishing lags, often one to two months long, official economic statistics have only recently began to reveal the magnitude of the downturn. But, much of the world economy is in the process of reopening. There is now some evidence that the trough in economic activity (due to COVID-19) may have taken place in April. As such, the focus of policymakers has shifted from ‘responding’ to the crisis to ‘recovering’ in a world still plagued by the virus.

Carefully balancing the health risks with risks of the economic kind will be of paramount importance. It would appear that the path forward is one where economies reopen gradually, alongside actions to minimize health risks, including testing, surveying, and tracing. There is little doubt that reopening will likely lead to more cases. But, a gradual lifting of restrictions, so as to not overwhelm the health care system, should help reduce economic scarring that often results when the downturn lasts a long time.

Importantly, not all countries are yet able to reopen their economies and are unlikely to begin recovering for weeks or even months. There is also a real risk of additional domestic outbreaks this year or beyond. Moreover, differences between countries in access to resources, economic structure, and fiscal capacity foretells a global recovery that will be protracted and very uneven. Better buckle-up, since it may be a bumpy ride.

We also want to stress that economic statistics will look astonishing as the recovery takes hold, despite its protracted nature. To illustrate the issue we need to consider the arithmetic: recovering from a 5 percent decline requires a rebound of 5.2 percent, whereas rebounding from a 50 percent drop necessitates a surge of 100 percent! In light of the severity of the global and Canadian downturns, even strong recovery numbers will leave the level of activity depressed.

As an example, the results of the Labour Force Survey in May indicated the Canadian economy added 289 thousand jobs. In typical times, even a tenth of that is very strong. But, the number pales in comparison to the more than three million lost in the prior two months. In fact, the gain still left the unemployment rate (including workers not looking for work due to health risks) at close to 20 percent. So, despite the base case forecast looking strong and almost ‘V’-shaped, the severity of the drop in economic activity means that this recovery will look more like checkmark or swoosh—a steep decline followed by a slow return to the prior level.

When thinking about the downturn and the subsequent hoped-for recovery,

particularly at the industry-level, we have considered a myriad of cyclical,

structural, and even non-economic factors.

Where do we go from here?

What has become apparent is that the unprecedented shock that is the COVID-19 pandemic has initiated changes in a number of sectors. It has also become a catalyst for ongoing trends in several industries and the economy in aggregate. Let us take a moment to highlight some of the key considerations.

Canada’s population is aging rapidly and is increasingly reliant on immigration for growth. Moreover, older Canadians face greater health risks and their savings have been impacted by financial market volatility. COVID-19 may reduce their labour participation and their willingness to spend during the recovery and beyond.

Canada still remains open to immigration, but may not be able to attract as many newcomers given the increased health risks of international travel.

Canada is committed to addressing climate change. There is an opportunity for governments to use their COVID policy actions to accelerate the shift to a less carbon-intensive economy. The federal government program to address orphan wells in the energy sector is a case in point.

Businesses and governments have been forced to accelerate their shift to digital. This will impact business investment during the recovery, but the changes to business processes may temper the labour market recovery.

Organizations have been shifting to flexible workplaces and promoting remote work. For many, the imposition of containment rules has made remote work a necessity. There are many studies on the increased productivity from remote work, including the time saving on commuting, but the shift that took place by government edict has been abrupt. Many workers and businesses were not ready for working from home. This was made more difficult by school and daycare closures. As such, labour productivity may have been reduced. Worker preferences aside, businesses will want to see the return on their investment to deploy the remote-work infrastructure. Many will also recognize the potential cost savings from commercial real estate. This spells trouble for commercial real estate prices and may dampen commercial real estate construction.

Similarly, due to the need to maintain physical distancing, some firms are expanding the use of automation. This could help boost business investment during the recovery, but also impinge on labour demand.

The rise of protectionism has been affecting global supply chains for years. But, the pandemic has severely disrupted supply chains in ways firms and governments never contemplated. As the recovery unfolds, many global supply chains will be altered. For example, some businesses are thinking about supply chain redundancy in case of future disruption.

Governments have become aware that it may be necessary to have certain essential products produced domestically. Restoring essentials (medical supplies and equipment) or strategic products (electronics, defence) should help future investment. But, the need for uninterrupted supply will need to be balanced with the diminished gains from trade.

The role of government has been greatly expanded. Governments are now responsible for managing and ensuring business work environments, such as distance between the restaurant tables or the height of plexi-glass partitions. Through the Large Employer Financing Facility, the federal government is taking a stake in businesses that make use of the program, while restricting executive pay and share buy-backs.

Geopolitical risks have increased. The tragic health toll and economic hardship wrought by COVID-19 have motivated many countries to take a harder line with China. While this may subside once the pandemic is eradicated, it highlights increased political risk during the recovery. Conflict between China and the West was likely inevitable, but political risks during a slow economic recovery are a bad combination.

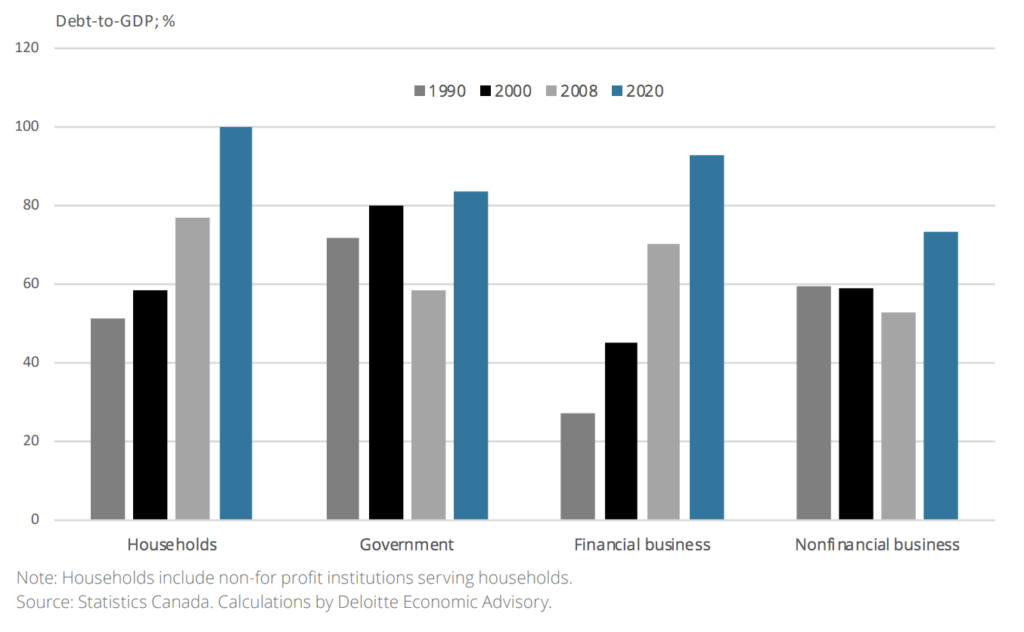

Debt-to-GDP; %

The key economic legacy of COVID-19 will be debt. Job losses and reduced hours have hit household incomes, making for highly indebted consumers—indeed, debt-to-income ratios are likely to rise substantially in Canada from already high levels (see Figure 2). Lower demand and additional costs of doing business will also indebt businesses. And, perhaps most dramatically, the cost of supporting workers and businesses during the downturn will leave governments laden with debt. The additional debt will likely temper the pace of recovery and leave economies ever more fragile going forward.

There may also be changes in how consumers behave during the recovery, particularly until a vaccine is deployed. Given the health risks, consumers are likely to make fewer trips to stores and be reluctant to touch products on shelves, make larger purchases per trip but in aggregate buy less.

The need for continued physical distancing will restrict how many customers can be present at stores, restaurants, and gyms. This will not only impact the volume of sales but will also limit the number of workers needed.

A key uncertainty is about how governments wind down the income and credit support programs put in place. For example, the CERB provides unemployed workers with $500 per week for up to six months. But, this program will eventually end. At that point, unemployed workers will need to be transferred onto Employment insurance support, but many workers do not qualify for EI. The government may launch an EI- equivalent program for those not eligible. But, these income-support programs are less generous that the CERB. Similarly, banks are offering mortgage deferrals for up to six months. That will help financially strained Canadians, but the deferrals will cease at some point. The implication is that we have only seen a portion of the income and unemployment shock. The same is true for business bankruptcies. In April, consumer and business insolvencies were lower than in March and down significantly from a year prior. However, this masks the true state of insolvencies, which are being delayed by the government in hopes of limiting them.

Finally, the Canadian recovery will also be shaped by the prospects for hard-hit industries. In many cases, the industries that are hardest hit will have the longest recovery. International tourism and air travel, for instance, will be severely restricted while the virus remains a concern. Retailers will have to adapt to even lower spending at brick-and-mortar stores going forward, while eating at home may become more frequent over dining out at restaurants (whether by preference or income constraints). The Canadian oil industry will continue to be challenged by excess supply and elevated inventory levels. Despite the likelihood of languishing prices, oil production will rise because of past investment and the prohibitive costs of restarting, but the impact on investment may never fully unwind.

Canadian outlook

When we consider all of the above, there is a strong case for a slow recovery.

Consumer spending accounts for nearly 60 percent of economic activity. Households may be cautious in their spending and the labour market recovery could take considerable time. This suggests only modest-to-moderate economic growth after the initial rebound from reopening.

Residential investment has thus far held its own during the lockdown, with new home construction particularly resilient. However, there is a real risk of a home price correction, with construction likely to follow. Higher unemployment, reduced personal income, continued health risks, and higher indebtedness are not positive for the real estate market. There is also a risk of a flood of condos held by investors onto the market as properties fail to provide adequate rental income. Commercial real estate (CRE) is especially vulnerable given the shift to remote work. Industrial and warehouse CRE will be less affected than retail or office CRE, but even with reshoring and e-commerce gains, it is unlikely to escape unharmed. Business investment will be constrained by financial losses, but essential investments in areas like digital and automation will continue.

Business investment should improve as firms address the heightened health risks and the economy recovers. But, as previously discussed, sectors such as energy will buck this trend.

Capital expenditures by the federal and provincial governments should be boosted by stimulus measures yet to be announced. Governments often prioritize infrastructure investment for stimulus since they have a high economic multiplier. We expect that instead of the typical roads and bridges, governments will choose to focus on digital, health care, and education.

Government spending will be solid in the near-term, but will likely be constrained as the recovery strengthens and governments start thinking about fiscal rebalancing. Realistically, this is a longer-term theme, unlikely to be undertaken before 2022 at the earliest.

Canadian international trade should recover alongside the global economy. Exports should also benefit from a US recovery and the possibility that some firms bnear-shore activities to North America. And, while the energy sector is expected to lag, it should benefit from the global recovery and less disagreement among OPEC+ members.

Given the massive fiscal and monetary stimulus, some worry about an acceleration in inflation. At the moment, inflation risks are low. In fact, risks of deflation are far more concerning given the magnitude of the recession. Inflation could rise if the amount of fiscal and monetary policy stimulus is not reduced once the economy is back on its feet. However, this is unlikely given the temporary nature of fiscal measures.

Here are few numbers

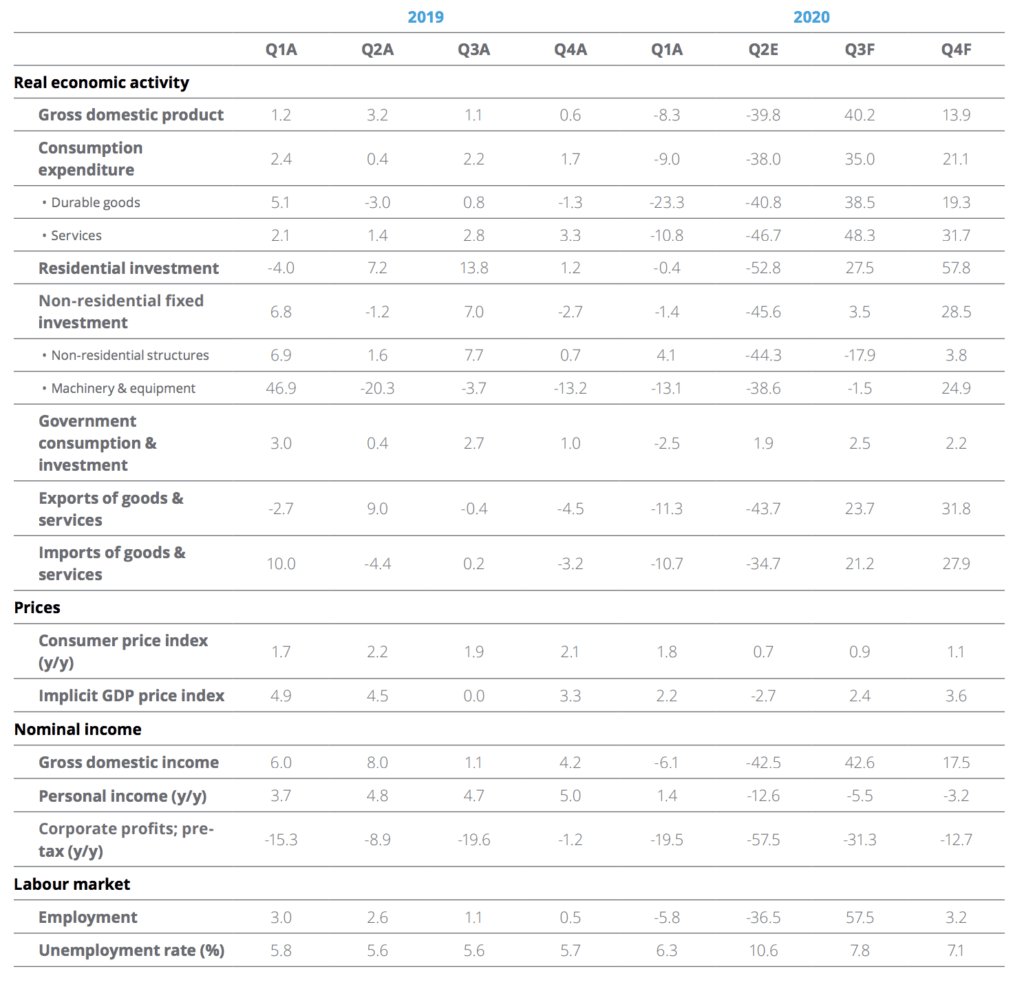

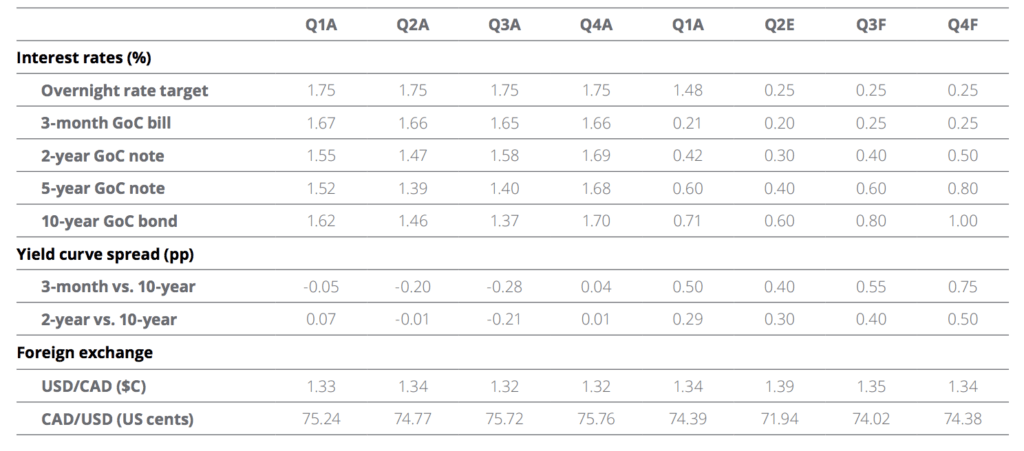

So, putting all of the elements together, what is the outlook for Canadian economic growth? After contracting by an annualized 8.3 percent in the first quarter of 2020, the economy is estimated to have plunged 39.8 percent in the second quarter. However, growth looks to have resumed in May, with the economy expected to grow by an average of 27 percent annualized in the second half of the year. For the year as a whole, the Canadian economy is slated to contract by 5.9 percent, before rebounding by 5.6 percent in 2021.

Canadian employment will drop 3.5 percent this year before rising 3.7 percent next year. While this may sound strong, the unemployment rate at the end of 2021 will still be well above pre-COVID-19 levels.

Reflecting the gradual recovery, the Bank of Canada is expect to keep interest rates at current levels until at least late 2021.

The Canadian dollar weakened earlier this year in reaction to declining commodity prices, diminishing economic prospects, and safe-haven buying of US dollar assets by investors. As the economic risks diminished and commodity prices stabilized, the Canadian dollar has rebounded to near 74 US cents at the time of writing this report. Looking ahead, we expect the loonie to rise slightly from current levels.

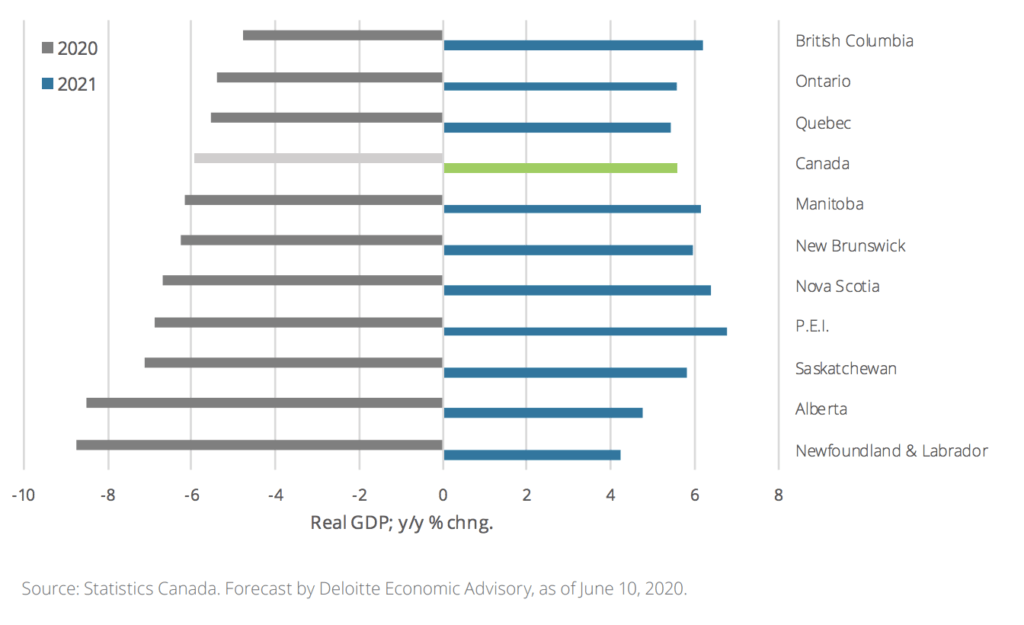

Provincial outlook

The Alberta and Newfoundland and Labrador economies will experience the most severe contractions in 2020, with real GDP falling by well above 8 percent, while Saskatchewan will see a contraction of near 7 percent. This poor performance reflects their high energy sector concentration.

The remainder of the Maritimes and Manitoba will decline by slightly more than the national average, while the central provinces of Ontario and Quebec will fare slightly better than the national average.

Lastly, the BC economy will be the outperformer, posting the mildest downturn and returning to pre-COVID levels the quickest. As for the recovery, gains in 2021 will be spread across all provinces, but the hardest hit will tend to be the slowest to recover.

Figure 3: Provincial forecast

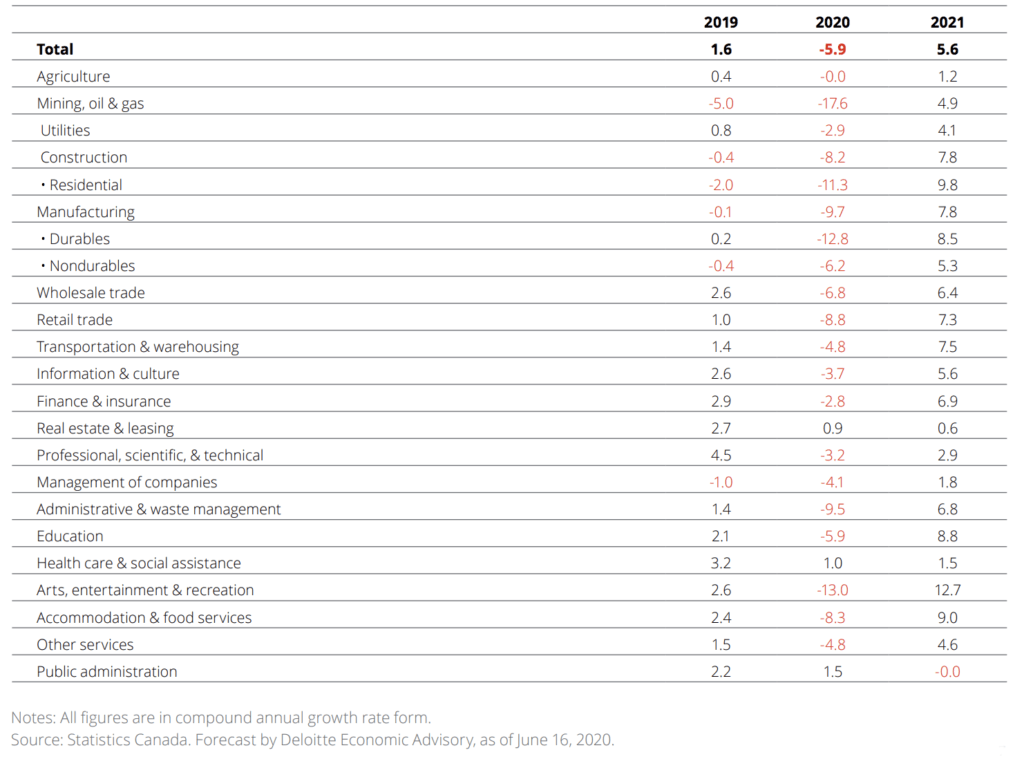

Industry outlook

The hardest hit industries include mining, oil and gas, entertainment and recreation, and durables manufacturing (such as autos).

All the above-mentionned sectors are expected to see double-digit contractions. Other industries that will be hard hit include retail, transportation, administrative services, accommodation, and food services.

Professional and financial services will see the mildest declines, given the ease of remote work. Lastly, two industries should post growth this year, with activity rising in health care and public administration tied to the fight against COVID-19.

The attached industry forecast table provides details of the downturn and recovery by economic sector.

Industry GDP forecast

Canada: Economic forecast

Canada: Financial forecast

Concluding remarks

The Canadian economy will suffer a deep recession this year, but the tide is already turning.

The key risk is a second round of infection, particularly if it leads to renewed lockdowns. So long as this does not occur, and the gradual reopening continues globally, a recovery should unfold in Canada in the second half of 2020.

However, the road to a full recovery, defined as economic activity reaching its pre- COVID-19 level, will take at least six quarters. This is due to continued health risks and the gradual nature of the economic reopening. It will also be hindered by expected weakness in the commodity sector.

The pandemic, lockdown, and reopening are fueling many trends that will not only shape the recovery, but will also affect the performance of Canadian industries. The recession will also leave behind deep and transformative legacies. For example, the additional government debt will be with us for years to come. But, it was the price to avoid a depression. The shift to digital, AI and automation, and remote work can be productivity enhancing, but may also have labour market consequences sooner than was anticipated.

Make no mistake, the fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic has been unprecedented in many ways. It is becoming increasingly apparent that its legacies may be unprecedented, or at least long lasting, too.

Schedule your retirement planning meeting today.

No Obligation & Confidential

Leave a Reply